Sorry for another semi used posting.

Ayano Chiba standing in her indigo field in winter.

Late 20s living in Japan, working as a English re-writer. Sitting by a fax machine in computer chip manufacturer while people handed me faxes in semi-broken English. I would patch up the English and fax away to the head office in the States. On the weekends I was studying Japanese ink painting and was getting orders to do paintings for interiors of Japanese restaurants. Every few months I would fly down to Java in Indonesia for a few weeks by myself and roam around. It was here I took a deeper look at the handwoven textiles from all the different islands of the archipelago. In villages I saw some women dying with indigo and natural dyes but it did not register exactly what they were doing or the significance of it. I took some batik courses and purchased ikats from over priced boutiques in Bali.

I was in a bookstore in Tokyo's Shinjuku one afternoon. I was looking for something. My bookshelves were overflowing with books and magazines on ink painting and pottery. I picked out the Shibori book by Yoshiko Wada, Mary Kellog Rice, and Jane Barton. I read a one page description of how Ayano Chiba the National Treasure planted her own indigo and processed it and dyed with it. I shut the book, snuffle chuckled and took it the cash register. 'OK. Now that the rest of my life is decided I can go have a beer.'

I was going to grow my own indigo and be an indigo craftsman. It seemed exactly right.

And I did. I got indigo seeds, grew, harvested and fermented exactly as was written in the book and dyed away.

Beginners luck I suppose. I have tried several ways to ferment the indigo leaves and the vat itself but I still do it the same way that Ayano Chiba did.

Her background set the criteria for what I figured a Living National Treasure should be. An anonymous person living in a backwater somewhere who had some skill that they had absorbed after a lifetime of working on it. She was doing it for the love of the process.

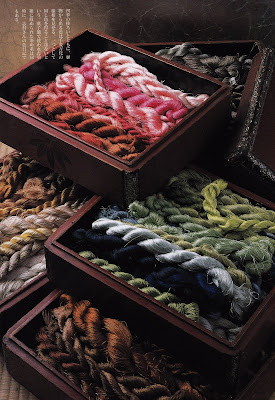

She was born in 1889 and passed away in 1980. She also grew hemp and processed it into threads by hand and wove it into kimono and then dyed the material. Her daughter carried on her work after her death.

I can see now that some Living National Treasures aim for the title and invest time and money in getting the status. They mostly deserve the recognition and it helps bring awareness to the value of culture to a country that often has it's priorities focused on surviving in this material society. There is a purity in Chiba san's compelling story though. Someone found her. She didn't go looking.