Persimmon tannin is used to make the traditional Japanese

katagami stencil paper and I use persimmon tannin later in the process to dye with.

Certain varieties of unripe persimmons are used for their high tannin content to make a traditional water repellent in Japan and Korea. (Perhaps, also in other areas in the world I am not aware of.) You run across articles on persimmon tannin processing in magazines and musty old journals on Japanese crafts. Inevitably the used-for-a-single-week-a-year-hand-cranked-fruit/persimmon squasher is pictured in the corner of a smelly barn along with rustic bamboo baskets overflowing with green persimmons . A farmer and his wife with cool dental work and

tenugui wrapped on their heads standing in front of wood casks of fermenting liquid proudly but shyly. The process is described but the real secrets of the trade, like how long the fruit is allowed to ferment and how the bad bacteria is killed and how it is filtered etc. are always left conspicuously out. I've never been able to make the high-quality stuff but make an unrefined (some say better, but I don't agree) instant version.

Our local band of monkeys climb up and steal the fruit this time of year and it is easy to collect the fallen squashies and grate them with a stainless cheese grater. Then squeeze out the pulp and use the juice to dye thread and cloth. It takes several weeks for the earth tones to come out.

The persimmon tannin liquid that is more stable than my home made version. There has been a boom in

kakishibi use the past few years and the price has dramatically come down. The slightly more expensive type from

Seiwa in

Takodanobaba is very good. They came out with a much less smelly version a few years ago. Why they still sell the rancid 'Eau de Poo' variety at the same price it is difficult understand. It used to be like buying a bottle of distilled diarrhea. Honestly.

Every house in the Japanese countryside has at least a few persimmon trees. At least one would be a sweet variety where the fruit can be eaten once it turns red in October. The others will be a very astringent variety that will be peeled and strung up from the outside rafters in the sun to make a sweet dried fruit. The leaves in early spring are used to wrap sushi in and contain some natural preservative that lightly flavors the fish. The trees themselves are a gorgeous part of the autumn scenery with the red fruit hanging form branches the farmers/monkeys couldn't reach. A few hang in there into winter for birds to savor.

The house with a few hanging/drying persimmons.

Persimmon dye needs ultra-violet rays to change into the golden brown color. You dilute the liquid one third to one fifth depending on whether you are dying thread or depending on the coarseness of the cloth and it's eventual function. Wet the cloth directly in the diluted solution and then place it directly on the ground or I sometimes put it on my metal kitchen roof. Snoopy loves to walk on it as it dries so precious stuff gets the roof treatment where Snoopy can't access it. You want as much heat and direct sun as possible. The tannin absorbs the suns rays and turns a crispy golden brown. One piece usually goes through this process at least 15 times. Thread of course is hung up.

It is impossible to get an even dye on thread. Just the areas the sun hits in the first few hours will turn dark.

I look forward to the dying season all winter and can squeeze in perhaps five weeks from mid-May until the monsoon starts and I start again in August when it lifts. The days are getting shorter now and there are only a few weeks left to dye at most. Last week that the color changes slower than it has been. The shadows are longer and it's sad not to be up at the crack of dawn with the daily routine of wetting the cloth and thread and arranging it in the sun to soak up the heat.

This same persimmon tannin has been used for hundreds of years to make a layered paper called,

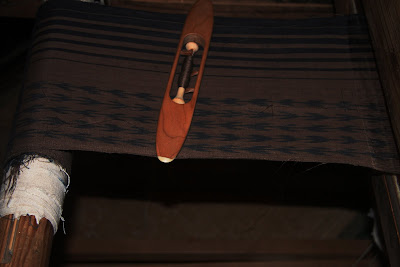

Katagami used for cutting stencils. Thin

washi (Japanese hand made paper)is covered with the tannin and several layers are added. (I have seen it made with newspaper and tannin as well.) It comes in several thicknesses. It is tough and when wet resembles leather to some degree. It can be punch cut or cutter knife cut. Some stencils require a fine silk mesh to be lacquered in place to enforce the stencil before it can be used. It has a distinct wood creosote smell. (Creosote is what they used to dunk railway ties in to preserve them. When making charcoal the sugar and liquid content of the wood goes out the chimney. The liquid can be dripped/distilled out of the flue easily.)

I am currently cutting out this stencil of lotus and leaves. I will use the stencil to make a kimono which has no shoulder seams. The pattern must face both up and down and look natural. Hmmm. The design on the edges must line up to make a repeating pattern. It is too Japanese folk-crafty for my liking but already I've invested a dozen evening beer and as many hours so I'll finish it up. I'll carve three stencils in total to resist in several startges. The flowers white. The pond dark and the leaves light blue. Still a lot of work ahead of me here before the pasting and dying even start. You can see the special hand made knife I use to cut the stencil out with.

There are a few large pots of lotus outside the front door and they are used as a motifs occasionally. They bloom only a few hours and then fade quickly. They are heavily laden with Buddhist meaning. Out of the mud comes purity... life is transient...kind of thing. Buddha usually sits on some kind of lotus platform and lotus are often swirling around somewhere in his halo or on his garments.

Here is a stencil I carved many years ago of willow branches behind a blind. It has been used so many times it has fallen to pieces. It is still possible still squeeze out a few more works once in a while. The stencil may be in shreds but it seems happy to be made use out of. Like dropping by for coffee with an old friend who isn't quite all there but seems to enjoy the company and reminiscing about younger days.

This wallet was made from some linen patterned from the falling apart stencil. Indigo and persimmon tannin dyes.